dnmusic

Sight-reading

Sight-reading is the process of converting musical notation into the sound the notation represents. We look at the notation and realize the music via our bodies and instrument.

The written music is input and the performed music is output. We ourselves are the machine that converts the input into the output.

How well are we expected to sight-read?

Most people assume that when reading music we haven’t seen before, we must be expected to stumble and make mistakes. We might have to disassemble the music into small segments and practice each segment dozens or hundreds of times before we are able to perform the music.

I disagree with that assumption. In my opinion, we should be able to play most Western music more-or-less correctly at sight. Exceptions include unusual musical genres that vary from the usual conventions, and music that is exceptionally challenging technically.

When we “woodshed” a piece, our goal is to polish the performance, not merely to learn the notes by rote.

Professional expectations

If you get to the point that you’re playing professionally, even part-time, the expectations will be different than they are in school ensembles. You’ll be expected to play all or nearly all the music correctly on sight, and in some cases you’ll be expected to transpose it on sight to accommodate singers whose vocal ranges differ from those for whom the music was originally written.

My teaching

My private teaching includes explicit practice of sight-reading with the goal to make the translation from notation to sound as automatic and natural as possible.

What makes this a realistic goal? A couple of things.

- western musical notation follows consistent conventions (read more)

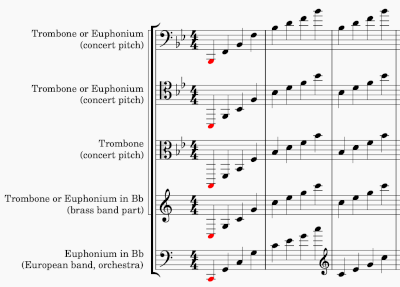

- transposing parts for brass instruments follow the same pattern (read more)

Euphonium/trombone notation

C clefs are not used in transposed parts. Transposed parts always use treble or bass clef.

Clefs may change in any given part as the music moves higher or lower.

Clues for sight-reading

Written music contains clues that can help us sight-read the music and not just the notes.

Even in an audition situation, which may be stressful, we have a couple of minutes to examine the music before we attempt to play it. We can identify potentially-problematic passages and mentally make a plan for the slide positions or alternate fingerings we want to use, before we start to play.

Where do we look for clues in the written music? I’ve prepared some examples to illustrate how we can find clues to help us sight-read music effectively.

In some cases I’ve written out the “plan” for approaching the music. Of course, we won’t write things out like that in real life. It’s only to illustrate what’s going on in our heads as we prepare to address a new piece of music for the first time.